In my earlier post, I mostly focused on the Upperclass and Upper Middle Class Victorian 5 O’Clock tea, which was very formal and had a specific etiquette to it. At the same time there was a less formal version of the formal home tea which might have been given in middle class homes, but also in less formal situations in Upperclass homes. The difference between these gradations being principally the number of servants who helped set and serve the meal.

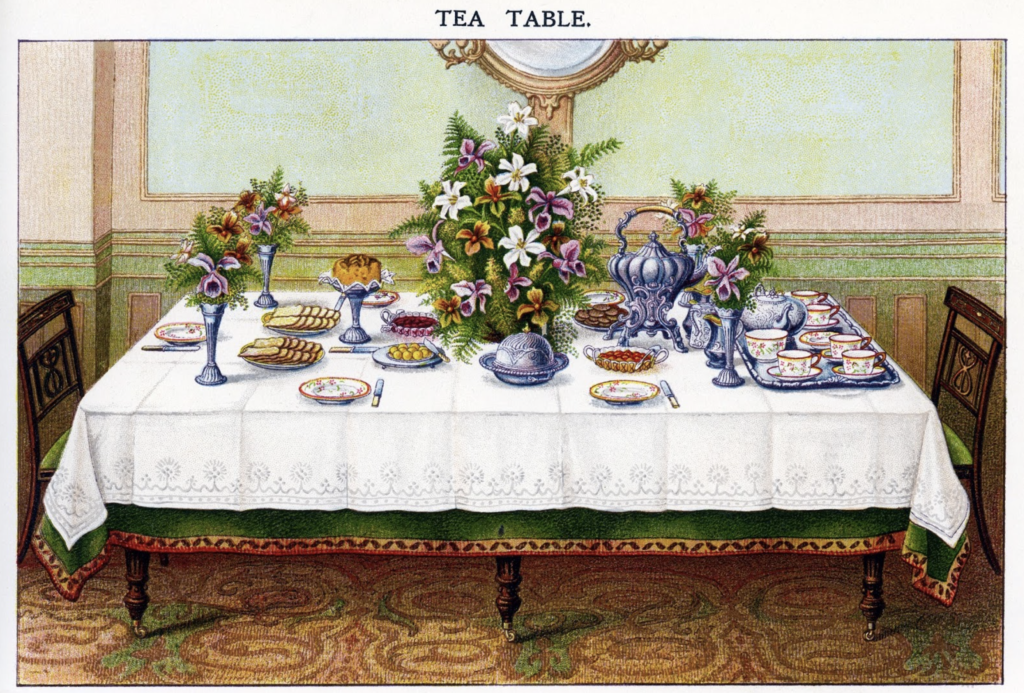

This is not to say that a formal tea would ever be servant-less until the mid twentieth century. Even a middle class 19th century and early 20th century tea would have had a maid of all works to assist in serving the tea. While most etiquette from a formal 5 O’Clock tea would have been observed there would be differences owing to the lack of help. Similarities would be that the lady of the house or a daughter would pour the tea for each guest. There would be a selection of sandwiches, finger cakes and biscuits/cookies. Where it might differ is that there would be a smaller guest list and guests might sit at the table, as seen above. This would only happen if the hostess had a limited amount of space to entertain.

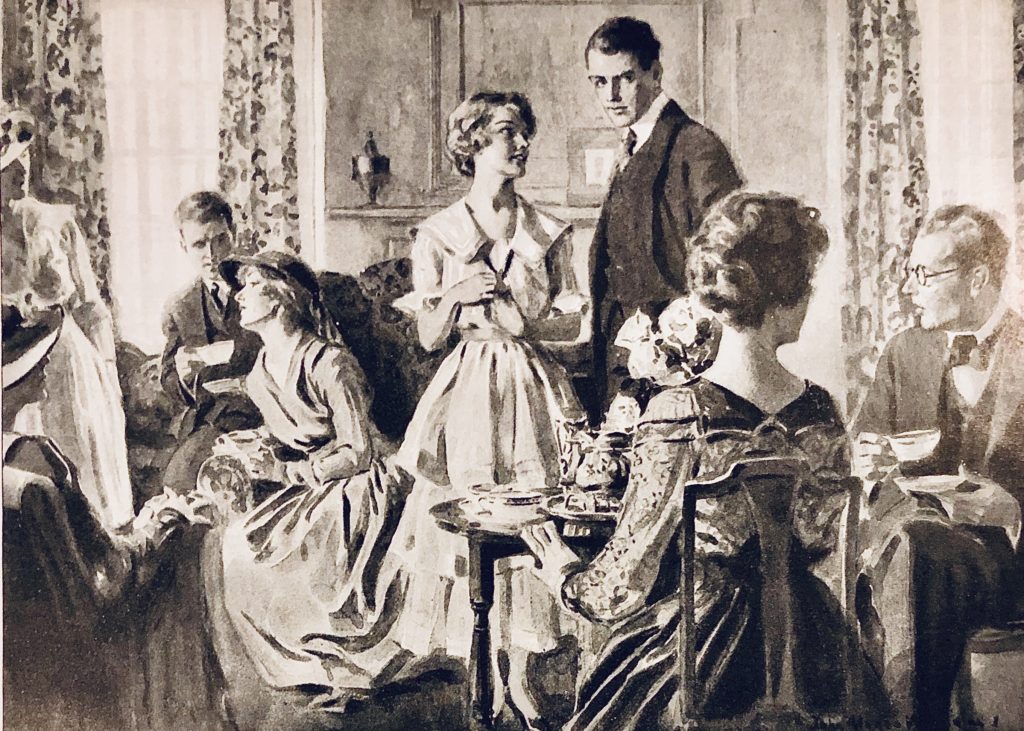

Even for the upperclasses, times changed and while the event continued being called a 5 O’Clock, over time the form and function changed radically. This is one of the hard things about etiquette, it really is always shape shifting and mutating into something new. So, as the Victorian era waned and the Edwardian age began, formality went on the decline. Upper class and middle class women stayed in school longer, attended universities in greater numbers and “gasp” even sought employment. This meant the days when women dressed six times a day to make endless rounds of visits, teas, luncheons, suppers, entertainments and balls had slowly, but surely, started to disappear. Only the very wealthiest continued in this fashion and even they weren’t completely immune as it was often the richest young ladies that could afford to continue their educations at university, or if not at school, with the feminine equivalent of a grand tour through Europe. Less women at home, meant less teas in the home setting.

Of course, the Edwardians did still entertain formally. Some would say the way they entertained was the pinnacle of elegance, but the reality is that the number of servants had already gone on the decline as jobs in factories appeared and the industrial revolution provided opportunities for the lower classes to improve their lives. The stiff decline in the numbers of people who went into service meant fussy extra entertainments which required excess labor were slowly phased out. By the time of the First World War, the Edwardians could no longer support huge staffs and so their entertainments began to disappear. Changes to the tax codes further eroded the wealth of the upper classes and the rise of ladies entertaining in restaurants, spelled the death of the formal five o’clock.

Class played a large part in who drank tea in America until the late twentieth century. While tea would never be the predominant drink in America, it was drunk more frequently by the upper classes. Partly because the very wealthy had long ties to England that went back to Revolutionary times and many never made the political shift to coffee that the rest of America did, some because they wished to mimic British society which remained steadfastly tea drinkers, and some because they hoped that by preferring tea to coffee they would appear more upper-class and cultured. Of course, there were also those who just preferred the taste.

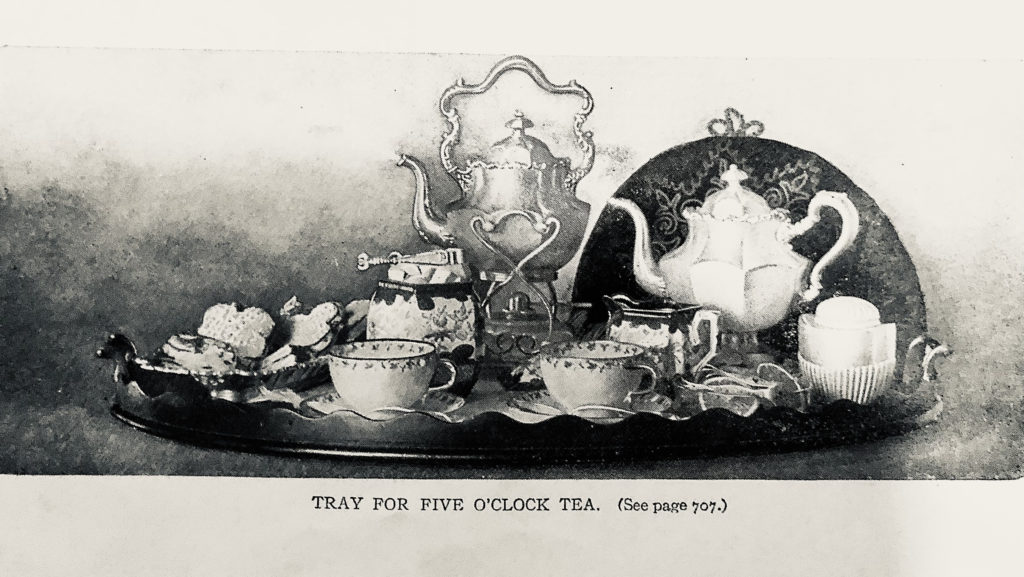

Because of the less common nature of the tea in the US, a Five O’Clock tea could mean the formal event described in my earlier post, or tea on a tray with only a small number of guests as far back as the turn of the century. While tea consumption in the US increased during the twenties, owing to prohibition, this was mainly in the form of black tea when drunk hot and even then Americans preferred their tea iced or in punch, (interesting fact, early in the 20th century, green tea was preferred for iced tea).

Without alcohol, the Five O’Clock became a cocktail party alternative for young couples, though again, this tended to be constrained to upperclass and upper middle-class homes.

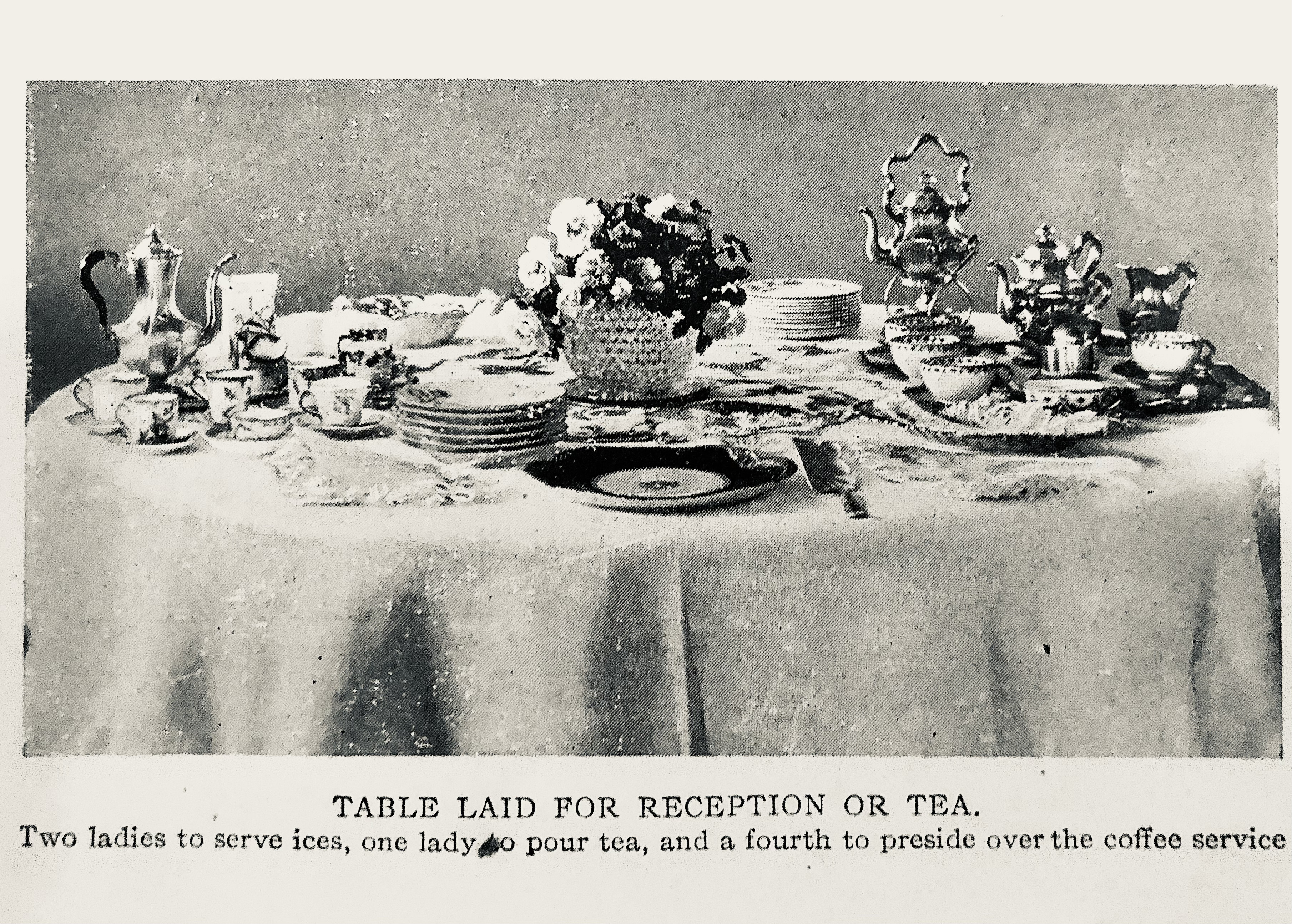

In America as Britain and Europe, formal Five O’Clock tea continued into the thirties, but grew smaller and more informal. Teas had always been a pastime of the very wealthy in America and while still quite fancy by our standards, an American Five O’Clock tended to have less than a dozen guests. More commonly, six or less. Because attendance was smaller, the freedom to enter late and leave fifteen to twenty minutes later was removed. With fewer guests, the Five O’Clock tea became more of a meal with less dishes, but larger portions. You may note that it looked more like the Victorian middle class tea. In some ways this was the precursor of what we might think of as the modern ladies home luncheon, especially when they were coupled with a presentation of some sort. Indeed, teas now almost always also involved coffee as well as tea, and were routinely called “receptions” having strayed so far in likeness from the original event.

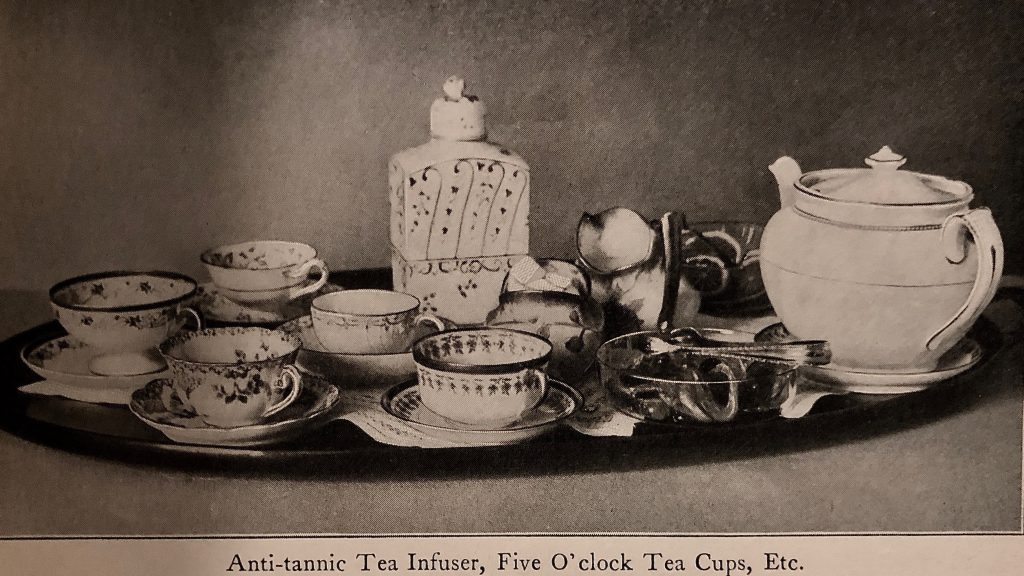

By the late thirties, the formal tea came to resemble a simple home tea, but with the requirement of fancy tea service sets. This meant that tea remained an expensive proposition, when it came to formal entertaining. Tea pots with cups, tongs for sugar, tea caddies and spoons, on and on – the average American wasn’t going to spend the money on items they would rarely use. And with the depression, fancy teas were out of the question for the average woman. It wouldn’t be until the late thirties that tea parties would begin move to the masses, and by then Americans would have changed the formal tea so that it barely resembled the original entertainment.

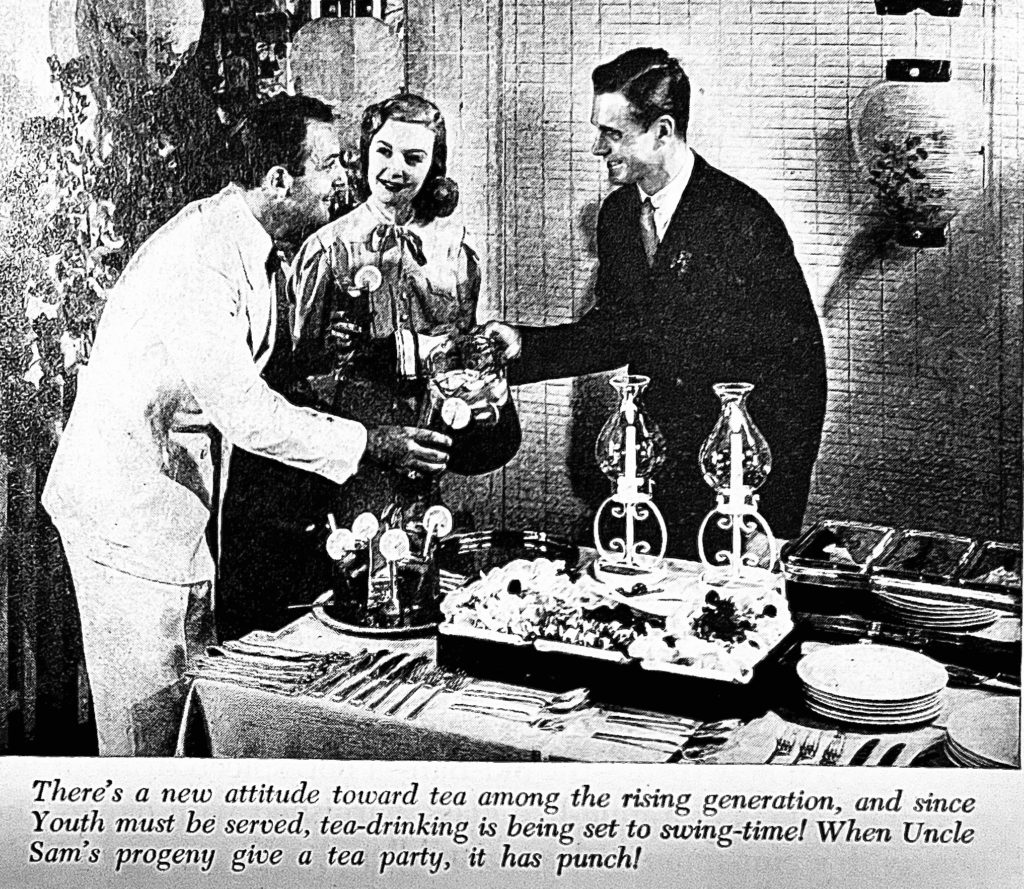

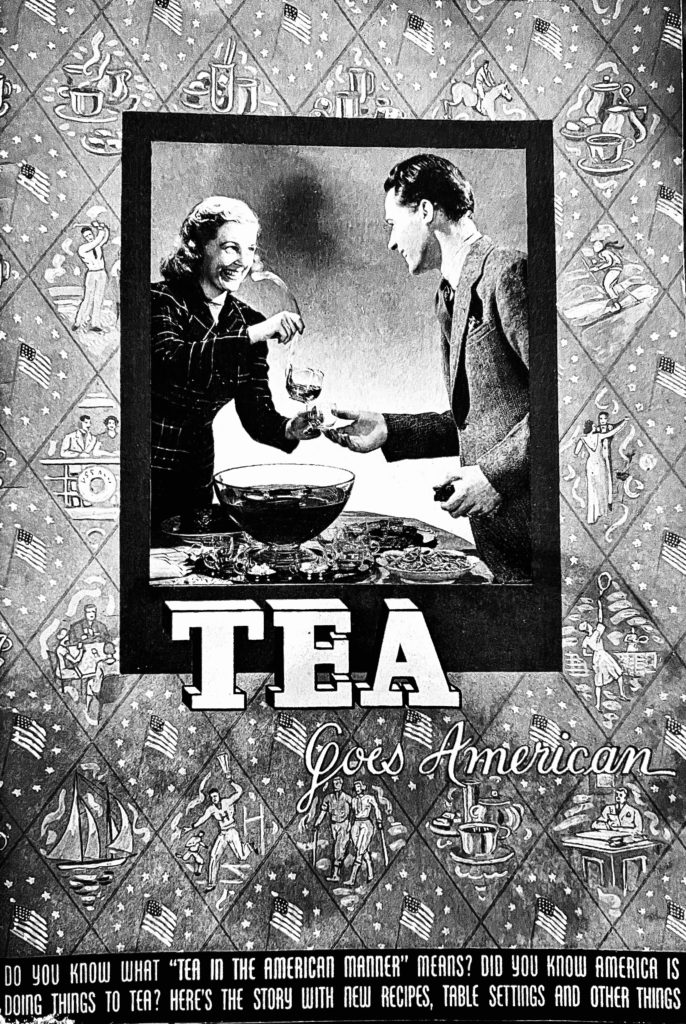

There was a push by tea companies to make Americans drink more tea in the 30s and 40s which resulted in tea parties becoming more “Americanized”. Men were now invited and as you can see from the wonderful brochure introducing the country to the joys of tea below, punch was added.

Chief change was the price point of a tea party. By serving punch or iced tea, one only needed a nice pitcher and repurposed cocktail glasses, this eliminated the cost of an expensive tea set. While practical, this rather ruined the idea of tea as a formal event, except in the sense that an American tea party became a teetotaling cocktail party. Despite these efforts, the dressy tea party really didn’t catch on with the masses and formal tea remained a niche event.

Tea drinking did eventually increase in the US, first after WWII when American saw the importation of Japanese tea and then and then in the 50’s after the Korean War. These events widened the types of tea Americans drank, introducing more exotic blends to a curious public.

After the Second World War ended and the 50s began, many Americans were flush with cash and had a hankering for social mobility. Formal afternoon teas finally became a popular way for women to entertain. Silver-plated tea sets became ubiquitous and were achieved at practically any price point. The men again were booted out, (with the exception of guests of honor, musicians and speakers). New and extensive rules of etiquette were introduced. Upscale tea parties became a symbol of middle class aspirations, held in homes, but also schools and ladies institutions. Formal teas became centered around political cause, social group or school function. Sometimes these coincided with early home sales of beauty products or fashion shows.

Formal home teas continued into the sixties, but by the 70’s they were beginning to seem pretentious and out of touch. There was practically no one who would have recognized the term, “a 5 O’Clock” and even silver catalogues which had featured 5 O’Clock spoons, no longer carried them. Entertaining was on its way to the more casual get togethers we all know today. Even amongst the very wealthy, the formal at home tea stopped being a normal entertainment and became a type of party given only for special occasions or in tandem with an event or luncheon.

How are you? I hope you’re all well, drinking copious amounts of tea and coffee. I’m absolutely addicted to Winter Spice tea with unsulphered dried ginger added to the pot. I hope you’re all keeping warm and toasty. Sending you much love.